Most financial controls fail not because people ignore them, but because they're applied to the wrong kind of transaction.

A wire transfer and a vendor payment might look similar in your ERP system. Both involve sending money. Both require approval. But they fail in completely different ways, and treating them the same is how organizations lose millions to fraud, errors, and preventable mistakes.

The problem isn't a lack of controls. It's a lack of classification.

🗂️ Classification Before Controls

Before you can secure a transaction, you need to name what kind of transaction it is. This isn't bureaucratic box-checking. It's the difference between applying the right level of scrutiny and sleepwalking through a high-risk payment because it looked routine.

Classification answers a simple question: What is the nature of this money movement?

The answer determines everything that follows: how much verification is required, who has authority to approve, how fast money should move, and what kind of oversight applies.

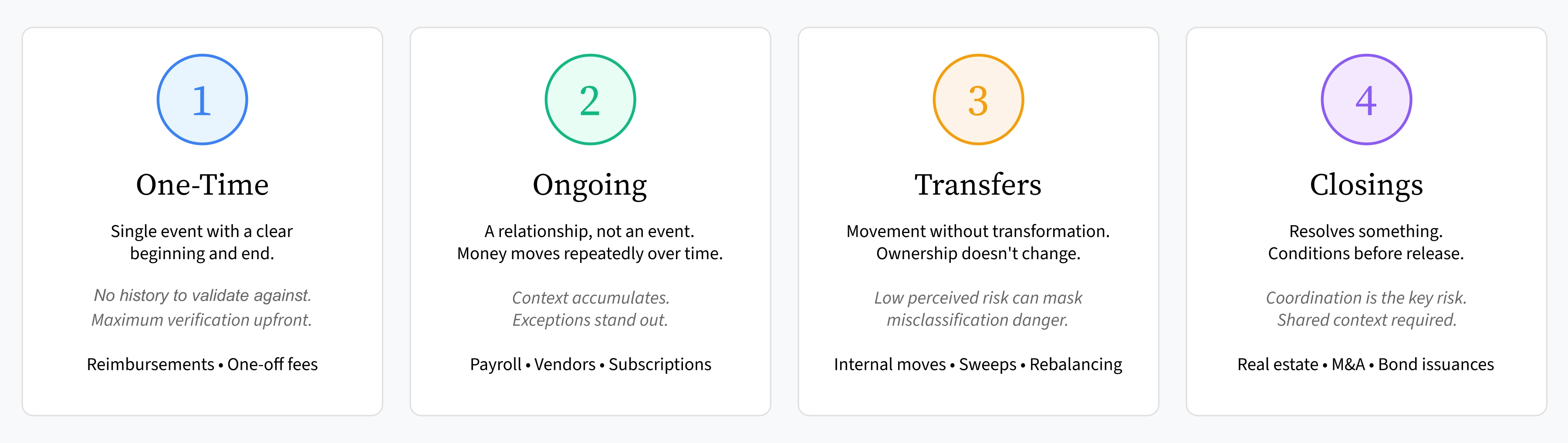

At a minimum, every transaction falls into one of four types.

1. One-Time Transactions

A one-time transaction is exactly what it sounds like: a single event with a clear beginning and end. A one-off reimbursement, a standalone professional fee, a single purchase from a vendor you don't expect to use again.

What makes one-time transactions risky isn't the dollar amount. It's the lack of history. There's no established pattern to validate against. No rhythm. Identity assumptions are weaker, and errors are harder to spot because nothing "looks wrong" yet.

This is where impersonation attacks thrive. A fraudster posing as a new vendor doesn't need to match historical behavior. There isn't any.

The fix: One-time transactions should trigger maximum verification upfront, independent confirmation of identities and accounts, and slower execution by design. When they're treated casually because they appear small, they quietly become some of the highest-risk movements of money in the organization.

2. Ongoing Transactions

An ongoing transaction isn't an event. It's a relationship. Money moves repeatedly over time between the same parties. Vendor payments, payroll, debt service, and subscription arrangements all fall here.

The strength of ongoing transactions is efficiency. Context accumulates. Identities can be established once and reused. Normal behavior becomes clear, and exceptions stand out immediately.

The most common mistake? Treating an ongoing transaction as a series of unrelated one-time payments. When that happens, context fragments. Every payment becomes a fresh decision. You duplicate controls or bypass them. Efficiency compounds when you recognize the relationship; chaos compounds when you don't.

The fix: Streamlined processes for routine payments, reuse of verified identities, clear thresholds for exceptions, and periodic re-verification to prevent familiarity from becoming blindness.

3. Transfers

A transfer describes movement without transformation. Ownership doesn't change. There are no conditions to satisfy. Funds are simply being relocated: between internal accounts, sweeping funds, rebalancing liquidity.

Transfers are often perceived as low risk. And when they are truly transfers, they can be. But that perception is exactly what makes them dangerous when misclassified.

The moment a "transfer" involves an external party, timing dependencies, conditional release, or irreversible finality, it stops being a transfer. Treating it as one is how internal trust gets exploited.

The fix: Clear confirmation that ownership is not changing, separation of duties for internal movements, and explicit verification even when both sides belong to the same organization.

4. Closings

A closing is a transaction that resolves something. Multiple parties must coordinate. Conditions must be satisfied before money moves. Funds are released alongside documents, approvals, or events.

Real estate purchases, M&A deals, bond issuances, capital raises, and major capital projects all involve closings. What makes them unique isn't the size of the payment. It's the coordination required.

When closings are treated like large transfers or rushed payments, participants operate in isolation. Assumptions replace verification. Speed increases risk instead of reducing friction.

The fix: Shared context across all participants, verification before release (not after), sequenced flows tied to conditions, and a clearly defined point of completion.

‼️ Why This Matters

When classification is wrong, transaction controls are misapplied. Low-risk processes get layered onto high-risk activity. Familiarity replaces scrutiny. Responsibility fragments. Risk remains invisible until it's realized.

When classification is right, the work gets easier. Teams stop debating process because they're no longer confused about purpose. Reviews go faster because context already exists. Exceptions stand out because they don't belong. Money moves quickly where it should, and deliberately where it needs to.

Different transactions behave differently. When you name them correctly, the system knows how to treat them.

Classification is one pillar of a larger system. The The Secure Transactions Framework shows how classification connects to hierarchy, sequencing, and the operational controls that make secure transactions possible at scale.